I'm thrilled to be able to announce at the reviews I wrote for the always-excellent Dark Roasted Blend just went up! To start, here's some quickie capsule reviews of some classic cyberpunk titles ... with others going up very, very soon.

(right image credit: Huxtable)

Neal Stephenson

Snow Crash

Considered by many to be the ultimate cyberpunk novel (or second only to Gibson's Neuromancer), Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash has everything the genre requires: high-tech toys and low-life characters, a flash and dazzle style, a noir beat, enough concepts and ideas for a dozen other novels, and heaping helpings of bad boy attitude.

Set in a run-down LA in an archetypal "not too distant future," the novel is basically the story of Hiro Protagonist (wink, wink), the "Last Of The Freelance Hackers And Greatest Swordfighter In The World" and ex-pizza delivernator for the mafia; and Y.T., a nimble and nubile adolescent "kourier."

In the course of trying to survive a world run by corporations, and where the endless suburbs are lit by the omnipresent loglow of franchises like Mr. Lee's Greater Hong Kong, and CosaNostra Pizza, Hiro and Y.T. stumble into a plot by billionaire villain L. Bob Rife to... well, rule the world using a special brand of information warfare with its roots in ancient Sumerian mythology. Along the way, Hiro and Y.T. meet characters such as Ng, the technofetishist weaponeer, and Raven Ravinoff, the nuclear bomb-connected Aleut harpooner and assassin whose preferred weapons are molecular-sharp glass knives.

Snow Crash, when it rocks and rolls, which it often does, is like strapping yourself in for a dose a blisteringly fast anime: a near-chaos of cyberdelic images, methamphetamine-fueled concepts, quick bursts of characters and characterization, along with flights of pure digital fantasy. For those new to cyberpunk, reading a chapter of Snow Crash is like taking a shot of science fiction espresso.

Luckily, Neal Stephenson also knows when to put on the brakes, to pull over by the side of his roaring information superhighway of a novel and let the rest of us catch up a bit. For all its flash and dazzle, Snow Crash also has some great moments of humanity. The scenes, for instance, with Y.T. and Uncle Enzo, CEO of the American Mafia and Hiro's ex-boss as head of CosaNostra Pizza, are charming without feeling cornball. Other characters, some of them only featured for a few paragraphs, manage the same.

Some have criticized Snow Crash as a perfect example of style over substance, sarcastically saying that it's cyberpunk's purest form. Sure, the book has some serious flaws – like when it slams on the brakes to lecture Hiro, and the reader, about Sumerian mythology's relationship to linguistics and human information processing. But what saves Snow Crash from being bubblegum and instead makes it a satisfying literary meal is the inescapable sense that Stephenson is not taking himself, the book, or cyberpunk itself, very seriously.

Snow Crash is, in its heart, a cartoon: a laughing, giggling, fun time. The heroes aren't heroes. The villains – for the most part – aren't villains. The Metaverse – Stephenson's version of cyberspace – is a bold and colorful place full of animated characters, and the real world the stages and settings are too bold and outrageous to be anything but Stephenson's elbow to the reader's ribs with a chuckle of "Get it?"

To press the point, just look at Stephenson's other novels. Some have the same pop and sizzle -- like The Diamond Age -- but after reading Snow Crash it gets pretty clear when he's going for serious and poignant and when he's taking us along on a digital, cyberdelic, outrageous, dazzling, bizarre, animated, good-time ride.

Set in a run-down LA in an archetypal "not too distant future," the novel is basically the story of Hiro Protagonist (wink, wink), the "Last Of The Freelance Hackers And Greatest Swordfighter In The World" and ex-pizza delivernator for the mafia; and Y.T., a nimble and nubile adolescent "kourier."

In the course of trying to survive a world run by corporations, and where the endless suburbs are lit by the omnipresent loglow of franchises like Mr. Lee's Greater Hong Kong, and CosaNostra Pizza, Hiro and Y.T. stumble into a plot by billionaire villain L. Bob Rife to... well, rule the world using a special brand of information warfare with its roots in ancient Sumerian mythology. Along the way, Hiro and Y.T. meet characters such as Ng, the technofetishist weaponeer, and Raven Ravinoff, the nuclear bomb-connected Aleut harpooner and assassin whose preferred weapons are molecular-sharp glass knives.

Snow Crash, when it rocks and rolls, which it often does, is like strapping yourself in for a dose a blisteringly fast anime: a near-chaos of cyberdelic images, methamphetamine-fueled concepts, quick bursts of characters and characterization, along with flights of pure digital fantasy. For those new to cyberpunk, reading a chapter of Snow Crash is like taking a shot of science fiction espresso.

Luckily, Neal Stephenson also knows when to put on the brakes, to pull over by the side of his roaring information superhighway of a novel and let the rest of us catch up a bit. For all its flash and dazzle, Snow Crash also has some great moments of humanity. The scenes, for instance, with Y.T. and Uncle Enzo, CEO of the American Mafia and Hiro's ex-boss as head of CosaNostra Pizza, are charming without feeling cornball. Other characters, some of them only featured for a few paragraphs, manage the same.

Some have criticized Snow Crash as a perfect example of style over substance, sarcastically saying that it's cyberpunk's purest form. Sure, the book has some serious flaws – like when it slams on the brakes to lecture Hiro, and the reader, about Sumerian mythology's relationship to linguistics and human information processing. But what saves Snow Crash from being bubblegum and instead makes it a satisfying literary meal is the inescapable sense that Stephenson is not taking himself, the book, or cyberpunk itself, very seriously.

Snow Crash is, in its heart, a cartoon: a laughing, giggling, fun time. The heroes aren't heroes. The villains – for the most part – aren't villains. The Metaverse – Stephenson's version of cyberspace – is a bold and colorful place full of animated characters, and the real world the stages and settings are too bold and outrageous to be anything but Stephenson's elbow to the reader's ribs with a chuckle of "Get it?"

To press the point, just look at Stephenson's other novels. Some have the same pop and sizzle -- like The Diamond Age -- but after reading Snow Crash it gets pretty clear when he's going for serious and poignant and when he's taking us along on a digital, cyberdelic, outrageous, dazzling, bizarre, animated, good-time ride.

(review by M. Christian)

K. W. Jeter

Farewell, Horizontal

Like most of Jeter's novels "Farewell Horizontal" is rich and vibrant, with amazing and engaging concepts, packed with imagination to spare, and populated with fascinating characters on bizarre yet human missions.

Set in a future where a large segment of civilization is living in – and on the outside of -- a monstrous building called Cylinder, Horizontal teases and tantalizes with a lack of detail, making the book seem more like a surrealist exercise than a traditional (quote) science fiction (unquote) novel. Still, there's enough intimate details present to draw you into Ny Axxter's strange world.

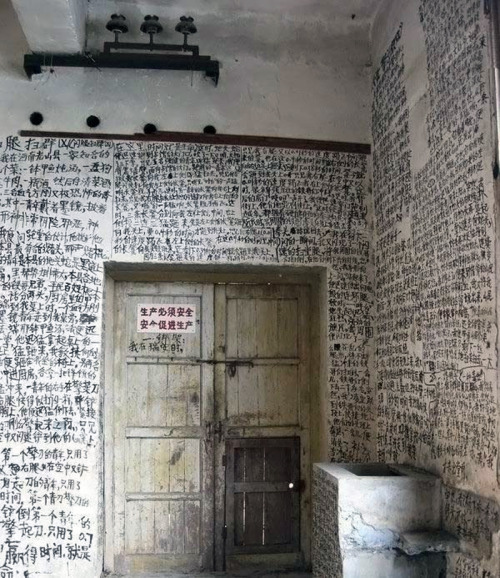

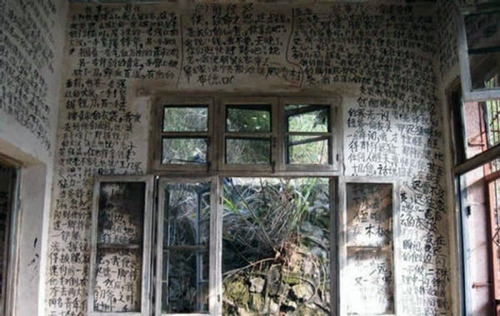

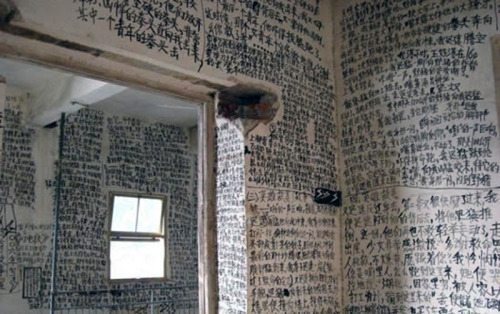

A graffex (which are sort of/kind of digital tattoos or markings) artist, Ny longs for the big time, a serious score that will lift him up – literally – from being a scavenging freelancer. And like everyone else who calls Cylinder home, he knows that his fame will come by not staying in the building, by being horizontal, but instead will come from what's on the outside, on the vertical.

The vertical is what makes Farewell Horizontal sparkle. Jeter has always had a brilliant imagination and with this novel, he lets it fly. Ny – and the rest of the outcasts and fringe folks of Cylinder – live their lives clinging to the building's staggering drop surface with a technofetish inventory of fun and interesting devices and technologies. It's when Jeter gets down – or up, as the case may be – with Ny and his life that the book really draws you in. You feel like you're there with him on the surface of the building, and when he sees what could be his score – a genetically engineered flying woman or 'angel' – you feel the exhilaration. The same goes when Ny is caught in a war between two warring gangs, a war fought on the same vertical he's trying to make his home. You are there alongside him as he tries to get through it all alive.

Unfortunately, Farewell Horizontal suffers from the feeling that it's just one part of a planned series, a series that was never completed: plot elements are left hanging, characters that are clearly meant to go somewhere go nowhere, and while the lack of details make the book refreshingly surreal (yet rich with cyberpunky elements), one gets the feeling that Jeter simply didn’t have the rest of the series he might have liked to set the stage and flesh out this fascinating world.

Still, Farewell Horizontal remains a very good book and deserves a read. While it might not be the perversely dark love poem to Philip K. Dick that his first book, Dr. Adder, was, or be a truly thought-provoking and sensitive book like The Glass Hammer, or – for that matter – a wickedly funny and strange thing like Infernal Devices, Farewell Horizontal is still more imaginative and vivid than many other books. If nothing else, it will change the way you look at skyscrapers … tripping your imagination into thinking what it would be like to live on the vertical and not just the horizontal.

#

Farewell, Horizontal

Like most of Jeter's novels "Farewell Horizontal" is rich and vibrant, with amazing and engaging concepts, packed with imagination to spare, and populated with fascinating characters on bizarre yet human missions.

Set in a future where a large segment of civilization is living in – and on the outside of -- a monstrous building called Cylinder, Horizontal teases and tantalizes with a lack of detail, making the book seem more like a surrealist exercise than a traditional (quote) science fiction (unquote) novel. Still, there's enough intimate details present to draw you into Ny Axxter's strange world.

A graffex (which are sort of/kind of digital tattoos or markings) artist, Ny longs for the big time, a serious score that will lift him up – literally – from being a scavenging freelancer. And like everyone else who calls Cylinder home, he knows that his fame will come by not staying in the building, by being horizontal, but instead will come from what's on the outside, on the vertical.

The vertical is what makes Farewell Horizontal sparkle. Jeter has always had a brilliant imagination and with this novel, he lets it fly. Ny – and the rest of the outcasts and fringe folks of Cylinder – live their lives clinging to the building's staggering drop surface with a technofetish inventory of fun and interesting devices and technologies. It's when Jeter gets down – or up, as the case may be – with Ny and his life that the book really draws you in. You feel like you're there with him on the surface of the building, and when he sees what could be his score – a genetically engineered flying woman or 'angel' – you feel the exhilaration. The same goes when Ny is caught in a war between two warring gangs, a war fought on the same vertical he's trying to make his home. You are there alongside him as he tries to get through it all alive.

Unfortunately, Farewell Horizontal suffers from the feeling that it's just one part of a planned series, a series that was never completed: plot elements are left hanging, characters that are clearly meant to go somewhere go nowhere, and while the lack of details make the book refreshingly surreal (yet rich with cyberpunky elements), one gets the feeling that Jeter simply didn’t have the rest of the series he might have liked to set the stage and flesh out this fascinating world.

Still, Farewell Horizontal remains a very good book and deserves a read. While it might not be the perversely dark love poem to Philip K. Dick that his first book, Dr. Adder, was, or be a truly thought-provoking and sensitive book like The Glass Hammer, or – for that matter – a wickedly funny and strange thing like Infernal Devices, Farewell Horizontal is still more imaginative and vivid than many other books. If nothing else, it will change the way you look at skyscrapers … tripping your imagination into thinking what it would be like to live on the vertical and not just the horizontal.

(review by M. Christian)

#

William Gibson

Virtual Light

It's interesting that after he finished his masterpiece Sprawl Trilogy of Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive, Gibson – the master not only of cyberpunk but of postmodern literature as well – would step back in time but remain in the future to write Virtual Light, the first of another three-part series, the so-called Bridge Trilogy.

Interesting, because Virtual Light is a fine and at times brilliant book that owes very little to science fiction, even though it has some elements in common. Set in a very near future, it follows the adventures of bike messenger Chevette Washington and disgraced cop Berry Rydell, who get caught up in a McGuffin chase when Washington impulsively steals a pair of special, high tech glasses. Their chase takes them all over California, most fascinatingly to a squatter city built in the decaying spine of San Francisco's Bay Bridge. Darkly comic, the novel has all of Gibson's trademark vividness and wickedly cool language but is much more of a noir novel with some surreal/science fiction elements than the ferociously dark and vicious Sprawl books.

Because of this, it's a much lighter and almost refreshing read, which threw a lot of Gibson's previous readers who may have been expecting something with a sharper edge. Still, when taken on its own or as part of the other Bridge books, Virtual Light remains a work by a master – a master who successfully took a different direction with a wonderful new book.

Samuel R. Delany

The Einstein Intersection

The Einstein Intersection

As with all truly great science fiction novels, The Einstein Intersection is less about science and more about fiction – in this case, fiction told by one of the greats not just of science fiction but modern literature as well.

Surreal doesn't begin to describe the setting and characters of The Einstein Intersection. Ostensibly about aliens exploring and trying to understand human culture after mankind has either left the planet or died off, the book is much more about some of the more powerful human archetypes. From Lo Lobey himself, a goat herder based on the myth of Orpheus, to the subject of his quest, Billy The Kid (AKA death), the book is a literary stage, allowing Delany to explore the world of our myths, fables, legends and fantasies.

It's unfortunate that people often pick up the book only to be frustrated and confused by Delany's psychedelic style. But for those with imagination and patience, reading The Einstein Intersection can swing open a brand new universe of style, language, and story: it's a wonderful book by a magnificent writer, first, and a great science fiction author, second.

J. G. Ballard

Vermillion Sands

I want to live in Vermillion Sands. I want to wake up in the morning and look out my bedroom window at the hypnotic world J.G. Ballard has created.

A collection of short stories, Vermillion Sands is set, mostly, in a Palm Springs-type vacation resort. There are two kinds of people there: the rich and the people who serve the rich. More importantly, though, the resort is a way for Ballard – in these stories – to explore the artistic process via a whole plethora of new technologies, from cloud sculpting to sound jewelry and more.

But Ballard is Ballard, so just writing stories about a resort, the people enjoying it or working there, or even the arts, is not enough: each of the stories in Vermillion Sands is also laced with his trademark psychological depth and lyrical subtlety. Sure, the stories might not be as subversively perverse, emotionally enigmatic, psychedelically strange, or horrifically languid as some of his other books and stories, but these light and almost funny tales are still J.G. Ballard – and that means they will always be as a brilliant and elusive as the landscape outside of Vermillion Sands.

(review by M. Christian)